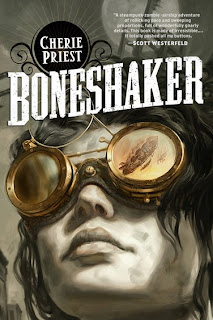

There’s a one word description for this novel that I think is very appropriate, and I hope people don’t think it too cruel: cute. Boneshaker is cute.

Boneshaker takes place in an alternate 1880, in an apocalyptic Seattle. Fifteen years earlier, a mad scientist named Leviticus Blue created a massive mining machine called the Boneshaker (in our reality, the name of a bicycle from about the same time). A test of the machine went horribly wrong and caused earthquakes that devastated the city and unleashed a horrible gas that citizens call “blight.” When the blight gas gets into people’s bloodstreams, through inhalation or other means, they turn into rampaging zombies. As a result, a massive wall was built around the city of Seattle to contain the zombie menace.

The novel focuses on Leviticus Blue’s surviving wife, Briar, and their son Zeke. The rebellious teenage Zeke decides to sneak into the city to learn about the fate of his father, and Briar goes to look for him on an airship run by pirates/drug-traffickers.

As a historian who works in this period, I do have a love/hate relationship with steampunk. I love that the novels tend to capture the sprawling and busy multiculturism of the nineteenth century in ways that most historical fiction ignores (after the first 50 pages, I was afraid Priest was using a lily-white cast, which would be pretty ridiculous in 1880 Seattle, but she soon introduced the diversity I expected). I also love the industrial aesthetic. On the other hand, steampunk really is more of an aesthetic than a subgenre; I often feel that everything is in service to the visuals. For instance, Priest takes time to explain that people need to wear goggles with polarized lenses to see the blight gas. Does this lead to a dramatic scene where a character loses their goggles, and finds them only to learn that they’re surrounded by blight? No. Is there some alternate history to explain why polarized lenses were invented 60 years early in this world? No. In fact, it never really comes up again, but it does mean that all of the characters are always wearing cool goggles. I’m probably nitpicking here, but it does bother me that steampunk scenarios so often miss the obvious opportunities to explore the real history in their settings while getting distracted by the scenery.

The novel also feels a bit too trendy. Steampunk is hot now with it airships and mad scientists. Zombies are also hot now, with hit films and their invasion of the western canon (Pride and Prejudice and Zombies). This steampunk versus zombies scenario is capturing something in the zeitgeist…but I’m not sure it will be as well-regarded when popular geek-taste moves along.

It is a well-told tale though. Briar and Zeke are likable, compelling characters, and the world was fun. There’s plenty of violence and darkness, but it’s really all in service of the steampunk/zombie aesthetic and the loving mother-son relationship at the center. It’s cute. And, a cute book certainly can win the Hugo award; it happened last year with Gaiman’s Graveyard Book. Do I think a cute novel should win the Hugo Award? I guess it depends on the competition.

Grade: B

.jpg)

.jpg)